Community-based research (CBR) has established itself as an effective way to engage participants and to get to the “truth” of the phenomenon under study, while minimizing the potential biases of researchers. Here, I offer 5 reminders to people who conduct this type of research, based on the experiences acquired in five multiple-year projects from 2015-present.

1) Practice reflexivity

It is an arts (and a science) to strike a balance between being involved with the project and being too involved. A lot of researchers are passionate about the research they do, some of them may have a vested interest in bettering the community they belong to. While this is a core element of CBR, researchers should remain objective and unbiased by “letting the data speak the truth” and “leaving an audit trail”.

2) Let the data speak the truth

From my experience working with researchers (or researcher activists) in the community, it is often observed (by me anyway) that some are so vested in the community that they are allowing their personal perspectives and beliefs to influence the outcomes from the data. For example, cancer treatment advocates may have a sweeping antagonistic view towards all existing government policies, or immigrant supporters may believe that the entire system is treating them unfairly no matter what. Remember, researchers are supposed to be unbiased in their quest to find the truth, and the truth can be found in the data.

3) Leave an audit trail

This means documenting the tactics you have used to demonstrate the results are not subjective and ungrounded. It is especially important when the researcher is intimately involved with the community. For more on how to leave an audit trail, refer to the classic “Constructing Grounded Theory” book written by Dr. Kathy Charmaz (2014). Here are some examples:

-visit the sites on different dates and at different times

-assign multiple data analysts (such as data coders) to “triangulate” the analysis

-calculate percentage agreement and/or Kappa score on coding done by different coders, to establish the research as “scientific”

-organize “member-checking” meetings with various stakeholders to disseminate results and receive feedback from the community

-create a table and/or a graph to visualize all the methods used to ensure objectivity

4) Plan “member-checking” activities

This means bringing the preliminary or almost final results back to the stakeholders such as community members directly affected by the issue under study, policymakers, and researchers to be informed and to give feedback. These meetings can happen more than once, for example, one at the halfway point of data collection, and another one when the preliminary results are ready. It is not a mandatory requirement in CBR but the quality and objectiveness of the study will greatly increase when member- checking is built into the research. Keep in mind that this is a time- and labour-intensive process to bring many parties together, so plan well in advance of these meetings.

5) Be ready to answer tough reviewer questions

The nature of CBR means that the research process could be unpredictable and the challenges faced would be unique to each project. Some common ones are an unexpected, prolonged period of data collection, or the difficulty in convening community members to meet to move the project along. Later, when you get to the writing and publishing stage, you may find the reviewers either know about the topic area well, or know about CBR well, but not both. As a result, be prepared to answer questions that may seem irrelevant, especially with regard to the following:

-What are the processes you have picked for YOUR community-based research?

-How did you ensure the data collection, data analysis and results are not biased and subjective? (Hint, the audit trail)

-What are some of the unique challenges in YOUR community-based research and how did you handle them?

Community-based research is not easy to do, but it could be a fun and enriching experience for both the researchers and participants. Remember, the research project lasts only a period of time, but the benefits that it brings to the community can last much longer. Have fun in this journey!

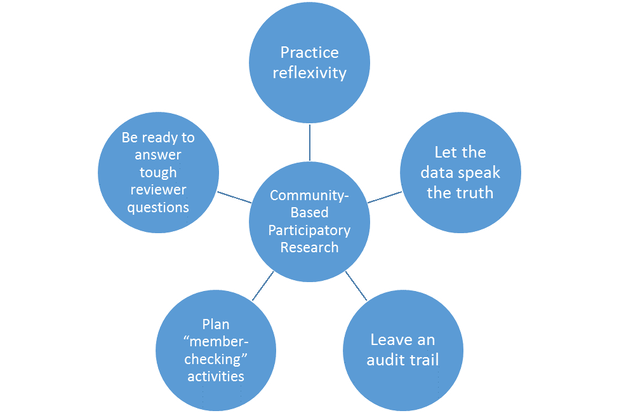

Figure 1 - 5 Tips for Conducting Community-Based Participatory Research

References

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

1) Practice reflexivity

It is an arts (and a science) to strike a balance between being involved with the project and being too involved. A lot of researchers are passionate about the research they do, some of them may have a vested interest in bettering the community they belong to. While this is a core element of CBR, researchers should remain objective and unbiased by “letting the data speak the truth” and “leaving an audit trail”.

2) Let the data speak the truth

From my experience working with researchers (or researcher activists) in the community, it is often observed (by me anyway) that some are so vested in the community that they are allowing their personal perspectives and beliefs to influence the outcomes from the data. For example, cancer treatment advocates may have a sweeping antagonistic view towards all existing government policies, or immigrant supporters may believe that the entire system is treating them unfairly no matter what. Remember, researchers are supposed to be unbiased in their quest to find the truth, and the truth can be found in the data.

3) Leave an audit trail

This means documenting the tactics you have used to demonstrate the results are not subjective and ungrounded. It is especially important when the researcher is intimately involved with the community. For more on how to leave an audit trail, refer to the classic “Constructing Grounded Theory” book written by Dr. Kathy Charmaz (2014). Here are some examples:

-visit the sites on different dates and at different times

-assign multiple data analysts (such as data coders) to “triangulate” the analysis

-calculate percentage agreement and/or Kappa score on coding done by different coders, to establish the research as “scientific”

-organize “member-checking” meetings with various stakeholders to disseminate results and receive feedback from the community

-create a table and/or a graph to visualize all the methods used to ensure objectivity

4) Plan “member-checking” activities

This means bringing the preliminary or almost final results back to the stakeholders such as community members directly affected by the issue under study, policymakers, and researchers to be informed and to give feedback. These meetings can happen more than once, for example, one at the halfway point of data collection, and another one when the preliminary results are ready. It is not a mandatory requirement in CBR but the quality and objectiveness of the study will greatly increase when member- checking is built into the research. Keep in mind that this is a time- and labour-intensive process to bring many parties together, so plan well in advance of these meetings.

5) Be ready to answer tough reviewer questions

The nature of CBR means that the research process could be unpredictable and the challenges faced would be unique to each project. Some common ones are an unexpected, prolonged period of data collection, or the difficulty in convening community members to meet to move the project along. Later, when you get to the writing and publishing stage, you may find the reviewers either know about the topic area well, or know about CBR well, but not both. As a result, be prepared to answer questions that may seem irrelevant, especially with regard to the following:

-What are the processes you have picked for YOUR community-based research?

-How did you ensure the data collection, data analysis and results are not biased and subjective? (Hint, the audit trail)

-What are some of the unique challenges in YOUR community-based research and how did you handle them?

Community-based research is not easy to do, but it could be a fun and enriching experience for both the researchers and participants. Remember, the research project lasts only a period of time, but the benefits that it brings to the community can last much longer. Have fun in this journey!

Figure 1 - 5 Tips for Conducting Community-Based Participatory Research

References

Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing Grounded Theory (2nd edition). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.